This web page was first mounted on November 16, 2015 and last updated on December 5, 2025 by Sheila Schmutz.

The Natural Retrieve: What's Natural About It?

Natural versus trained retrieves are common phrases in the hunting dog literature. A dog retrieving naturally does so without "force training to retrieve". Those looking for more insight than opinions, often refer to the wolf, the acknowledged ancestor of all dogs. Two forms of retrieving are recognized for wolves:

We’ll all agree that feeding young is both desirable and natural for both dogs and wolves. Yet we do not want our hunting dogs to cache food for future use – that’s why we hunt with cooperative dogs and not wolves.

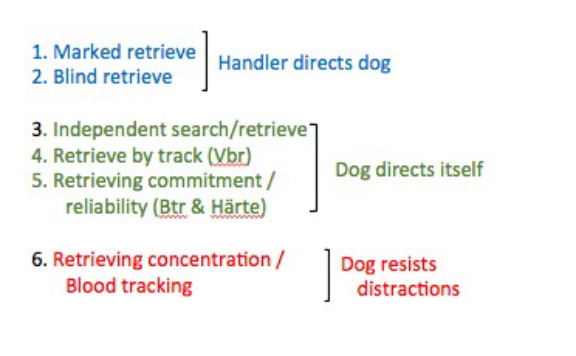

The chart above shows six different elements to retrieving or recovery of game by hunting dogs. Each element involves a more or less different task and, similarly, more or less different motivation that a dog brings to it. These differences do not have sharp boundaries, but rather blend into one another. We should be explicit as to which task we mean when we talk about retrieving.

The six dogs in the photo show nice retrieving manners, actually delivery-manners. They sit and hold patiently for me to take a photo. They do so until I put my hand on the frozen Hun, pigeon or antler and say "Out". At times they turned their heads while sitting. There may have been a noise or scent coming out of the woods. The dogs display more cooperation than obedience since they’ve never been forced to hold patiently. They did not drop even when their attention was turned elsewhere.

These six Sunnynook LMs have never experienced an ear pinch, a toe loop or an electronic collar in connection with retrieving. They contradict the oft espoused notion that reliable retrieving must be enforced via "force training". I could wax poetic even emotional describing some phenomenal retrieves they made in hunting. The dogs succeeded when I felt at times recovery was not possible. Such persistence by dogs can’t be trained.

If not trained retrieving, what these dogs do have instead is crucial. They have a pedigree full of ancestors that have proven several of the six listed elements of retrieving in a field test. In their case it was the Advanced Hunting Aptitude Evaluation (AHAE) of the Versatile Hunting Dog Federation. For these dogs, this test was required for breeding, among other things.

Selective breeding works. When properly practiced, it's given us modern hunting dogs that are essential for ethical hunting and would be the envy of hunters past. Why would we replace selective breeding with the lesser solution of retrieving enforced via force training?

|

The puppy pictured here counts three of the six dogs as ancestors. The 11-week-old Sunnynook's Kua already shows cooperative retrieving, an element that can't be enforced by training. It has to come from the dog within. On one of its walks in the woods, the puppy found a yearling-deer skull. It dropped the wooden stick it was carrying and picked up the skull instead. It carried the skull for 300 m, sometimes pushing it through understory brush and prickly roses, before it left the skull behind when something else caught its attention. More importantly, when I stopped and looked at the pup it kept walking up to me, making eye contact. This pup has the rudiments of cooperative retrieving. It carried it totally trusting that we are in our efforts together. I was careful not to undermine that trust. If a hunter with such a pup is careful to respect that pup's natural stages of behaviour development and never breaks this trust, there is the promise of a long and fruitful hunting relationship. |

|

Joe Schmutz, 18 April 2024

Krokus, Aiko, and a Village

They were barely out of the vehicle when Krokus von Kleinenkneten took a bee-line into the willow-bordered semi-permanent pond bordering a canola field. "Zeni" (Sunnynook's Zenaida) took a slightly different cast and when she came behind Krokus into the scent cone, she froze respecting Krokus' up-front position. As I walked past Krokus, the "Huns" (Gray Partridge) bailed out of their willow cover too far for a shot – typical behaviour in late season and on windy days.

I think that this challenging event with flighty birds at the start of the hunt galvanized both Krokus and Zeni to be extra careful. As planned, they searched small patches of cover singly for the rest of the day.

That day I hunted differently. It’s not my favourite kind of hunting, to drive on Glen's stubble field, walk under good wind up to a slough, and then drive on to the next one. It can be productive, and energy saving for me, but where is the enjoyment? Where is the exploration of the glacial moraine landscape, the native grasses and shrubs, and the glacial-erratic rocks deposited everywhere, with some re-arranged long ago into Tipi rings? According to Google Earth, I still walked 2.8 km through five spots of prime cover with gun in hand behind the dogs.

The dogs were phenomenal. Zeni was on point on one flock of Huns that came up through a small set of aspen trees. There was such a whirr of birds, dodging branches, I never got a good line on any of them. Krokus was working the largest patch of cover, where I bagged the two Huns and one young-of-the-year sharp-tailed grouse. One Hun was young too, but the other was an adult male, the dad of the 10-bird family group.

Krokus and Zeni had several points. It appeared that the strong wind was an advantage, able to move bird scent in the dense cover. The young male Hun fell into tall slough grass with the spot open and visible. Krokus had it right away. The adult male Hun fell in dense, human-height cattails. My heart sank, and then I mentally chastised myself for not waiting until the Hun had cleared the impossible cover.

I encouraged Krokus, to start her search just a bit down-wind of where the Hun fell, and then stayed out of the way, waiting quietly. She could not see over the cattails to see the fall herself. Soon enough, I could hear her pushing through the stiff cattail stems and abrasive leaves. The Hun must have moved some with its broken wing – I could have hugged Krokus as she came out with it.

The sharp-tail, fell deep into the base of willow bush at the cattails’ edge. Without the dog, I would have had next to no chance of finding it. As I think back, Krokus has always shown a good nose and knew how to use it. I guess performance-based breeding really works.

|

Krokus, as a German import, has a pedigree full of dogs that passed field tests proving complete hunting-level performance on land and water, before and after the shot, as all LMAC-bred dogs do too. There are good hunting dogs afield that have a few champions on the pedigree mixed with lesser qualified or untested ancestors. Why might the successful Versatile Dog breed clubs be so insistent on full hunting-level testing prior to breeding? I think it is because of the breadth of performance that we expect in fully Versatile Dogs: hunt upland birds in open country and forest, search, point and retrieve, track a cripple when required and fetch ducks out of water. That is a tall order, not expected of every hunting dog. That diversity of hunting tasks also includes some drives/motivations that border on opposing tendencies or contradictions. Such as, an energetic and rangy search followed, instantly after the shot, with the need for calm and deliberate tracking. Or, alternately pointing and tracking followed by a well-marked fall and a cooperative retrieve. Considering these opposing tendencies, the late Ed Bailey said that Versatile Dogs need to manage their split personalities in the field day in and day out. That successful managing by the dog of the split personality, the split tasks, is as important a goal for Versatile Dog breeders as a productive search or successful tracking. |

Krokus has had three litters. All were good with 4 or more puppies tested. Her last litter, Sunnynook’s J2, with Aiko von Sundorph, was exceptional. We had placed her 10 puppies with hunting families from Ontario to British Columbia. We always encourage our owners to test their dogs in the hope that some will become qualified to breed. The preparation involved also makes for better hunting dogs in the field. We like to say “It takes a village to raise consistently high quality Versatile Hunting Dogs.” With J2, the village-idea truly worked. Eight of the 10 pup owners did their part beautifully and brought their pups to NAVHDA or VHDF-Canada’s Hunting Aptitude Evaluation at 15 months old. Some of the owners were old hands at versatile dog training. For others this was their first Versatile Dog. The test scores are shown below.

The first thing to recognize is the commitment of the owners. Some drove two days just to get to Saskatoon. The second is the consistency, as mentioned, that all eight puppies passed what LMAC considers evidence of a promising, young hunting dog. Third, all the young dogs showed at least “good performance in all four hunting tasks, including search, pointing, tracking and water work.” Three of them entered the water in a search mode twice right off the bat when no enticement was thrown.It’s nice to see stellar scores - the group of eight had those too. For example, Jaeger's 11 points in tracking was because she tracked the running pheasant over 100 m, pointed it, and then retrieved it.

|

Yet, perhaps the best success of a breeding program comes from solid performances across a litter. These are the dogs that go hand-in-hand with ethical and satisfying hunting. With them we can rest easy in the evening, the dog’s head on our knee in the knowledge that all downed birds are in the bag, and later on the dinner plate. |

|

We applaud the breeders who raised Krokus and Aiko, and the hunter-owners who exposed and brought their young J2 dogs. All of these achievements are clear evidence of a successful village!

Joe Schmutz, November 2023

Recently we received a message and a YouTube link from Evan Paulhus, the proud owner of Sunnynook's Greta. He had just compiled the action sequences his GoPro camera had collected while hunting upland birds in southern Saskatchewan in fall 2020, before moving to Vancouver.

Not only do the sequences show Greta's ability in finding birds, but also cooperative pointing. Her retrieves were perhaps most impressive. Given the cover, Greta could not see all the birds fall and yet she did a remarkable job by persisting, expanding her search and using her nose to find dead falls or runners.

Greta is still a young dog, 2.5 years at the time. Greta had passed the Hunting Aptitude Evaluation (HAE) and Advanced-HAE in the Versatile Hunting Dog Federation-Canada (VHDF-Canada) testing in the "Very Good" category. This preparation for the practical hunting-oriented subjects of testing probably helped Greta to mature so early and become a capable and cooperative partner in the field.

Evan is maintaining Greta's training by reminding her to hold and deliver to hand. Like many hunters, Evan lets Greta go for the retrieve on the wing. Roosters no doubt had learned to evade predators many timesIn the dense and tall reed canary grass growing in dry pond beds.

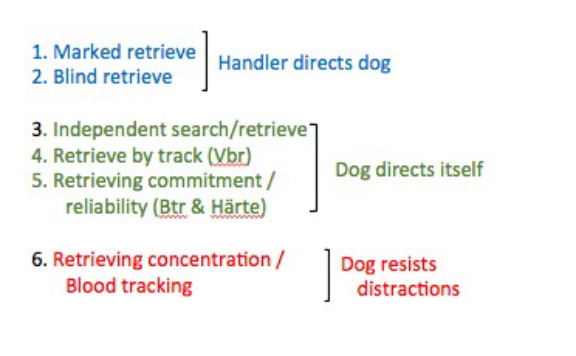

Greta is a pup from Sunnynook's 33rd litter out of Sunnynook's Bobwhite "Bobbi", sired by Sunnynook's Cue "Q". Both parents passed the demanding Performance Evaluation in the third level of Versatile Hunting Dog Federation field testing. Actually, of Greta's 30 ancestors on her pedigree, 24 have proven hunting performance at the Utility Test, Performance Evaluation or Verbands-Gebrauchs-Prüfung level. All 30 ancestors have passed a conformation test to ensure they look like a LM should and are constructed physically to be able to cope with the demands in the field, season after season.

Well done Greta and Evan! Enjoy watching their video!

video by Evan Paulhus, June 2021: text by Joe Schmutz, 21 June 2021

|

From the Sunnynook G2 litter of eight puppies, six owners stayed in touch with us and reported on the rich hunting they enjoy with their dogs. Spread from Manitoba to British Columbia to Idaho, the dogs have hunted Canada geese, Ruffed Grouse, Blue Grouse, Gray partridge and Pheasants. Some of them have already been field, health and conformation tested, providing a good chance that those that satisfy our performance requirements will go on to breed to help maintain the working dog tradition. The parents, Sunnynook’s Bowhite "Bobbie" and Cue "Q", have earned a Progeny Performance Award for this litter by having at least four puppies pass a Hunting Aptitude Evaluation or Natural Ability Test. We congratulate the young dogs, their parents and their owners! by Joe Schmutz, 23 February 2020 |

2019: 100 years of the LM as a breed, but how many cumulative years of service?

As of 2019, the LM as a breed is 100 years old. But how many dogs were there, and what might be their cumulative years of professional service? For the four dogs in the group picture below, it amounts to 25 years. More details follow about these 4 LMs.

Sunnynook's Uli was born in 2007 and joined Ray and Jeannie Collingwood in BC. Now at 12 years old she has been retired, taking it slow after 10 years hunting quail in Arizona, geese, ducks, sharp-tailed grouse and Hungarian partridge in Saskatchewan and mostly ptarmigan in the Spatsizi Wilderness of Northern British Columbia. When not hunting she patrols the yard and house near Smithers for black bears or entertains guests at the lodge of Collingwood Brothers' Guides and Outfitters, see "A working girl"

|

Sunnynook's Abby was born in 2013 and followed in the footsteps of Uli. Abby has hunted 6 years and is still going strong. Abby has the distinction of having saved a hunter's life, see Lodge Client: "Abby saved my life!" |

|

Sunnynook's Bobwhite "Bobbi"" was born in 2014 and still lives at Sunnynook. She has hunted for 5 years: sharp-tailed grouse, ruffed grouse, Hungarian partridge and pheasants in Saskatchewan, some ducks and geese and even snowshoe hares. She has also joined Uli and Abby in BC and hunted ptarmigan. |

|

Sunnynook’s Cue "Q"" was born in 2015 and joined Rick and Pat Schryer in Saskatoon. Q has hunted 4 years and typically starts the season hunting waterfowl over a large spread of decoys. Q and his hunting partners, Bones and Scotty, have learned to lie still among the decoys and begin retrieving when Rick gives the OK. The most impressive retrieve I have seen is when all the fallen birds had been collected by Bones and Scotty, yet Q was nowhere to be seen. Soon enough, he came out of the fog carrying a drake mallard. Q has learned to spot birds that are crippled among the many that flare away from the shooting, and follow the weakly flying cripple until he can catch it on land or in water.

Combined, these four dogs have provided 25 years of service. The quality of hunting they have provided for their owners and hunting guests is immeasurable. Ethical and truly enjoyable hunting is impossible without them.

by Joe Schmutz, 9 November 2019

Bobbi Goes Guiding

Spatsizi Wilderness Vacations’ (www.spatsizi.com) fishing and ptarmigan hunting has grown in popularity year after year. Clients spend three days fly-fishing for trout and grayling and then hunt ptarmigan for three days. This year, Ray Collingwood knew that his Sunnynook’s Abby could not be expected to hunt ptarmigan for all these clients in this tough mountain terrain. When the offer came for Sunnynook’s Bobwhite “Bobbi” and me to help out, the answer was obvious. We drove to Smithers and were flown from there 3 hrs to Spatsizi Lodge on Laslui Lake in north-central British Columbia. Spatsizi means land of the red goat in the Tahltan native tongue; the goats’ white coat turns red from lying on the iron-oxide-rich soils. Sheila and I and Larry and Meredith Miller had hunted there with Muddy Waters’ Buteo and Sunnynook’s Xyla "Minnie" in 2014 so I knew what to expect.

Willow-, white-tailed- and rock ptarmigan exist in this 6500 km2 Spatsizi Wilderness, that has no roads but many creeks, lakes, and mountains. The region is drained by the Stikine River which flows through the Alaska Panhandle to reach the West Coast. White-tailed, and especially willow ptarmigan, can be found in the spruce forest openings below the 1600-2000 m plateaus, but rock ptarmigan prefer the higher elevations. Spatsizi clients are drawn to a variety of vacation packages ranging from big game hunting to nature interpretation and photography out of a 5-star lodge setting. Bobbi and I were to hunt the summer-brown willow ptarmigan that flash white wings when they flush, their call resembling a person laughing.

|

We knew Bobbi could hunt. After all she’d hunted in Saskatchewan. She also passed the VHDF tests with flying colors, including the comprehensive Performance Evaluation. But, how would she cope with the other demands: flying in airplanes, riding in boats, negotiating saddle and pack horse feet on narrow and brushy game trails, leaving marmots alone and especially being smart during the ever-possible grizzly-bear encounters? Could she last a week hunting after running 12 km alongside horses to a spartan satellite camp with several-km outings each day? Would her pads hold up in this rocky alpine tundra? I was pleasantly surprised and each one of the four clients who came to know her well was smitten by her intelligent personality and her hunting savy. |

Horses Our team included saddle horses for a guide, a wrangler, two clients and me, plus two pack horses. Once we set off on horseback from Laslui Lake uphill, I kept looking for Bobbi and talking to her, telling her I’m still here - just a few feet off of the ground. The clients and guides also looked out for her when she was out of view in the dense dwarf birch along the trail.

Bobbi hunted continuously as we rode along, but never strayed too far despite her passion for all the interesting scents around. After the first ride, I put a bell on her and that helped provide peace of mind. Every so often, Bobbi would work some scent off to the side and fall behind. She then ran to keep up and gave me a near heart attack when she re-entered the trail mere centimetres in front of the lead horse, at least so it looked from my vantage point. She insisted on being in front. One horse in the string seemed to dislike dogs and seemed to taunt her, but that horse was moved to another group on the second trip to the plateau.

Running birds Ptarmigan have a reputation for running on the open tundra rather then taking to wing. While nearly all ptarmigan ran a few steps before takeoff, only a few required a push. It appears, when the dog is around their normally ground-bound predilection changes. Staying close to ground seems to work for ptarmigan. Twice we watched large falcons circling overhead, once for several hours, taking long dives at the family groups we flushed. Each time, the ptarmigan crashed back into dwarf birch or the stunted spruce clusters and avoided capture.

|

Dog work The basic search-point-retrieve with ptarmigan was essentially the same as with other game birds. Because of the ptarmigan’s ground orientation and despite the sparsely vegetated and open tundra, the birds held well. This gave us many opportunities to shoot over a point. If crippled, ptarmigan can run well and especially liked to hide in the nearly impenetrable wind-stunted spruce thickets of the tree-line. Bobbi kept her cool throughout. When we returned to the satellite camp after a day’s hunt, Bobbi lay on her pillow, groomed a cut or two she had suffered and slept. After several days, she was clearly worn out. Yet, when the horses were saddled each morning and especially when guns came out, she stretched and her normal always-on hunting spirit came back. In all, we estimated that we had 193 willow ptarmigan flushes and we bagged 64 amongst us. Our satellite camp may have been spartan on the surface, yet it was well enough equipped for us to savour ptarmigan heart, gizzard and liver as hors d’ouevres, breasts and legs as part of our meals. Bobbi enjoyed the remainder of the carcasses. |

|

The clients The hunting clients tend to be well-to-do folks who often lead high pressure lives and come hunting to get away from it all. They have hunted in many parts of the world, it seems. Some make use of all the hunting time they can get, others also lean back and simply take in the ambiance.

My secret concern about having my dog injured by a careless shot evaporated. All four of them came to love Bobbi and thoroughly enjoyed watching her work. When Matt once sang Bobbi’s praises to me, I said, yes, I agree, I love how she hunts, I only wish she was not so hard on the birds she retrieved. “Oh, well,” Matt said, “She’s got to have some fun too.”

by Joe Schmutz, 29 November 2018

Lodge Client: "Abby saved my life!"

The surprise encounter with a grizzly could have ended badly, had it not been for Sunnynook's Abby!

After the client had hiked, camped and hiked some more, he bagged a mountain caribou in the spectacular Spatsizi Wilderness of northern British Columbia. This allowed another hunting option during his stay, to spend a few days in a satellite camp and hunt ptarmigan on one of the many cordilleran plateaus above the treeline. An early big-game finish is not unusual in this spectacular mountain wilderness, dubbed the Serengeti of Canada. The region holds stone sheep, moose, mountain caribou, mountain goat, grizzly bear and wolves. The three lodges are efficiently run by members of the Collingwood family Guides come from far and wide to work with one of the best in the business.

|

Sunnynook's Abby joined Ray and Beannie Collingwood in 2013. Abby’s main job, like Sunnynook's Uli before her, is to greet guests, alert them of bears and wolves - unless the riding/pack horses do it before her, and, of course, hunt ptarmigan. On that fateful day, the client was dropped off down the lake to wait with Abby for the guides to bring packhorses around on shore and the rest of the gear in the second boat load. Together they were then to hike/trail 3 km through spruce forest to one of the 16 satellite camps nestled among the stunted Krummholz at the edge of the treeline. Near the lake, where the client and Abby were waiting, dwarf birch soon gave way to spruce forest. Visibility was limited. Suddenly, Abby sprang into action with a growl as a grizzly bear was coming toward them. No doubt the smell of food even though still packaged and snug on the packhorse saddle was attractive to the bear. The hunter only had a shot gun and bird shot that would have been a disaster did he have to use it. Abby kept pressuring the bear relentlessly, staying deftly out of reach. She threatened just seriously and persistently enough to make the bear eventually re-think the bacon smell and energy bars. Begrudgingly, the big bear ambled back down the creek bank and into the forest. |

|

Photo: In all likelihood, this photo is of the grizzly Abby stood ground to. It must have moved to higher elevation to feast on the many berries that had ripened on the tundra. |

| Photo: Abby’s favourite occupation. Greeting guests is her second favorite and standing bears and wolves her very, very distance third. |  |

The horse trail to the satellite camp lead right along the creek where the bear reluctantly disappeared to. Once the wrangler arrived with packhorses and the boat with remaining supplies, the group reconsidered. Instead of crowding the bear any further, they decided to postpone the ptarmigan hunt. Back at the lodge, a couple of Scotch calmed the client’s nerves. That evening the client heaped lavish praise on Abby, he truly believed she might have saved his life. |

Loyalty. What helped Abby save the day was not just pure aggression, but primarily an instinct to protect her human companions, a sound temperament and above all intelligence. Some dogs will run to protect themselves, others will hide behind the hunter. Abby did neither. Devlin Oestreich calls it loyalty. Devlin and Bill Oestreich own an outfitting lodge 1 hr. or so NW of Collingwood’s as the raven flies. Their dog Sunnynnook’s Vista, like Abby, has put black bears up into trees allowing the riders to get past without a mini rodeo and the risk of being bucked down-slope by spooked horses. Vista, like Abby and Uli, guarded the lodge and its guests, and provided peace of mind to parents when young children were out and about.

|

For Abby, that time was not her first encounter with grizzlies. Every so often, a cow moose and her calves will be pursued by grizzlies or wolves and the moose sometimes seek refuge near or even in the lodge area. On one occasion, a moose with two calves tried to outswim a grizzly right past the boat dock. The guides intercepted by boat and caused the grizzly to return to shore. The frustrated bear stood 100 yards from the lodge looking it over for a possible, alternate source of food. Abby placed herself between bear and lodge, barked and stood her ground, until the grizzly opted to return to the willow and dwarf birch flat down the valley. |

|

Photo: Here Abby is telling three wolves to stay clear of the Lodge and surroundings. Luckily for Abby, the wolves decided to comply. |

Citizen/hunter scientists. Grizzlies are becoming more common and moose less. The Collingwood’s hunting guides and support staff spend much of each year in the region and became intimately familiar with its wildlife over three decades. Their observations are from camp stays, during the many days of guided hunts, and from horseback or flying to and fro in small airplanes. The guides make it their business to know where the wildlife’s home ranges are and what the number of young is in a particular year. In years past, it was common for them to see 5-10 moose in a day. All too often in recent years, a cow moose with one or two calves one day will be alone in her home range later. This, coupled with observed kills or their carcass remains, tells a story.

The guides estimate that grizzlies and other large predators have taken 75-80% of moose calves in recent years. These observations could be enormously useful for those interested in nature conservation, and those devising wildlife and human management strategies. Bowing to public pressure, British Columbia has recently closed hunting of grizzlies. This closure was not just in areas of high human and low bear densities but province wide.

Of course, grizzlies and wolves need to eat too. Our society now holds a much more mature view of predators, compared to the days of simplistic bounties and 'the only good predator is a dead predator'. In their review entitled “Questionable policy for large carnivore hunting” Scott Creel and others point out that ".. policy must be considered within the area to which it applies."

Gathering the data needed for sound management decisions is time consuming, in need of a long-term perspective and costly. Here, local observations can be immensely helpful and represent a valuable contribution by hunters to wildlife science. Knowledge has been gained over years by the Collingwoods and many others outfitting for hunting, fishing, photography and nature interpretation. Scott Creel and others conclude that "Well-regulated hunting of large carnivores can yield costs and benefits for conservation but requires attention to both". One of the costs can be human safety; after all, there is only so much protection from bears Abby can offer.

by Joe Schmutz, 23 March 2018

Lassie Qualities of Sunnynook's Macaw

On January 20, a Canadian Broadcasting Corporation newscast mentioned an Alberta couple spending the winter in Arizona, whose Border Collie/heeler cross saved a life. The woman was riding a young, spirited horse when she was thrown and dragged until the stirrup broke and released her foot. When horse and dog returned home alone, with a broken stirrup, and when the dog was agitated wanting to lead, a search party followed on quads. At one junction, the dog clearly did not want to go on the trail the husband thought his wife had chosen, so they turned and followed the dog instead. In short, according to the doctor, blood loss from being dragged 400 m would have been fatal had the family dog not lead the search party the 5 km distance where the woman lay unconscious.

Lassie saved lives as a matter of routine, but of course she had a good trainer who taught her the individual behaviour sequences that came together only on TV. Researchers in animal behaviour have undergone a sea change when it comes to dogs' cognitive abilities, e.g. Scientific American Vol. 24 #3. Primates used to be considered the intelligentsia of the animal world but studies increasingly confirm what observant dog people long knew. The intelligence, cooperation, planning and compassion that dogs can display toward humans is nothing short of amazing.

|

This newscast reminded me of a feat by Sunnynook's Macaw "Mac". Here no human, but a Bobwhite Quail's life was on the line. While hunting some years ago in the Flint Hills of Kansas by invitation of Janice and Ron Franks (Cedar Ridge Kennel). I'd lost sight of Mac. I waited and called, but having already fallen well behind the rest of the hunters I decided to move on and let Mac find me. When I finally saw him coming he was behaving oddly. He made persistent eye contact and slowed his approach staying well behind me. His manner told me that he was trying to tell me something. Risking falling yet further behind, I turned and followed him. With a renewed spring in his step he lead, but stayed within sight, not searching but going from A to B. After about 300 m, he went on point at undergrowth where oak had been cleared. As I walked past him, the covey rose and I managed to drop a Bobwhite Quail. Everything about Mac's manners was purposeful - he must have left point at last, came to find me, got me to follow him and went on point again. I was in awe at what had just happened. I also was deeply grateful and proud of my long-time hunting companion. At the same time, I found it a humbling experience. After all, we humans think we're in charge - are we not? |

|

Photo: Sunnynook's Macaw "Mac" (1999-2011) is holding his Bobwhite Quail in the tallgrass - oak woodland quail habitat of the Flint Hills in eastern Kanas. |

Mac's was not an isolated 'break point temporarily to alert owner' incident. Mac's son Muddy Waters' Buteo handles birds very well and simply points until I decide he's been out of sight too long and retrace my hunting route to find him. Last fall, Buteo and Sunnynook's Veery were hunting well ahead and over a rise. One gets a sense of how long one's dog is comfortable being out of sight before it returns. Veery and Buteo's absence was longer than expected and when we changed direction to try and find them, Veery was still pointing the Ruffed Grouse that had ventured into sharp-tail country. Buteo came toward us over the rise with this meaningful and prolonged eye contact - had he just broken point to find us? As I flushed Veery's bird, Buteo stayed behind me, not going on to search as usual. The ruffie got nervous with Veery apparently pointing it at 20 yds for many minutes, and allowed me only a far shot, which I missed.

The late Jan Smith reported a similar event with Sunnynook's Huchen on an exercise walk in the country. When the sun set and Jan turned to head home, he'd walked some distance before he saw Huchen coming slowly over the rise staring at Jan. When Jan turned back so did Huchen. As Jan came over the rise, Huchen was on point. Jan walked ahead and flushed the paired, early-spring Huns.

Jan was well schooled in the principle of parsimony and not given to snap judgements when interpreting animal behaviour; the topic of his research and University teaching. Still, he was convinced that his dog acted out a mental plan involving deferred gratification, not simply chasing the partridge up. Instead, Huchen opted for the joint dog and human goal of having Jan flush and possibly shoot enabling a retrieve. This is evidence of complex mental processing, not formerly attributed to animals.

As a breeder I might ask myself how could we foster such intelligence and cooperation in our dogs. I have too little experience to know, but for starters feel that beyond a sound level of intelligence a cooperative spirit toward people may be helpful. The dog in overdrive, or as the description goes, 'a hunting machine', may not readily balance conflicting motivations. Such a dog may not be able to suppress one or more deeply seated behaviours such as the drive to pursue game. The adaptive cooperation may be most pronounced in hunting dogs that typically satisfy a variety of tasks, especially if these tasks may entail somewhat contradictory motivations such as pointing and retrieving. Herding dogs may provide a similar example. They have sufficient passion to crowd or even nip a large animal at the dog's possible peril, yet hold off and stop the chase when the animal moves in the desired direction - just when the chase looks like fun.

Researchers point toward a special bond, they call an attachment relationship, that underlies intelligent dog-human cooperation. It may be most promising to give the breeding nod to the intelligent, flexibly versatile and cooperative canine. Careful selection in breeding should likely be matched by a nurturing type of training, instead of the hard-nosed non-slip approach often touted. Whether hunting or herding, the dogs that hone their mental acuity in their regular work routine, may be mentally equipped to break pointing to communicate a plan to the hunting partner, or to lead rescue crews to fatally injured loved ones.

by Joe Schmutz, 28 Jan 2016

The Pointing Gene

In this impromptu training photo, Sunnynnok's Cue, Dryas and Dizzy are pointing a pigeon that is about to fly off and return to its home coop. One of the pups needed a gentle tug on the check cord to stop creeping, but every pointing-dog enthusiast will recognize instantly what is happening here. The pups are acting on an age-old canine instinct to stop and localize before the pounce. In this case of a breed that has been bred for pointing among other versatile dog traits for over 100 years, the stop has been prolonged and ritualized into an unmistakable pointing stance.

Cue, Dryas and Dizzy are pointing firmly and naturally at a mere 4 months of age. While no experienced breeder of versatile dogs will doubt that pointing is heritable, Professor Jörg Epplen and his team at Ruhr University in Bochum, Germany have recently substantiated this using a complex series of studies in molecular genetics. The article is authored by Denis A. Akkad, Wanda M. Girding, Robin B. Gasser and Jörg T. Epplen, entitled "Homozygosity mapping and sequencing identify two genes that might contribute to pointing behavior in hunting dogs" The authors focused their studies on four main breeds that are pointing (Large Munsterlander and Weimaraner) or herding breeds (Berger de Pyrenées and Schappendoes). They also used seven other pointing breeds for comparison, with 244 individual dog samples in total.

The authors showed that a region of DNA located on Chromosome #22 appears primarily responsible for pointing, while a region on chromosome #13 appears key in giving herding dogs their herding instincts. Of course, genes do not function in isolation, a truism that many casual observers of genetics and even dog breeders tend to forget. The single pointing gene identified here is part of a large complex of cellular and developmental machinery in the dog's body. A gene is necessary for a behavior to occur, for a bone to grow or a hair shaft to develop, but a gene alone is not sufficient. This is relevant for dog breeders in connection with the second key observations that Epplen and his team report, the differences in the versatile breed's origins.

Interestingly, The German Shorthaired Pointers compared in this study did not show the pointing-gene pattern in this same Chromosome 22 location. Clearly this breed has a pointing gene too but it is apparently in a different location in the genome, possibly with a different complex of cellular and developmental machinery associated with it. The authors point out that Large Munsterlanders and Weimaraners on the one hand, and German Shorthaired Pointers on the other, have different historic origins.

The international kennel club, Federation Cynologique Internationale or FCI publishes translations of the original breed clubs' century-old breed standards, #99 for the Weimaraner, #118 for the LM and #119 for the GSP. Under breed origins, the breed clubs for Weimaraner and LM both point to a hunting dog type of 200-plus years ago, broadly described as "Hühnerhund" or upland bird spaniel, and the GSP club to "Braque or hound".

Far too little of these breed origins is recorded for our benefit but several authors have painstakingly scrutinized the records and offered a glimpse into why and how they were developed. In "The art of medieval hunting: The hound and the hawk" John Cummins, (1988, Castle Books, Edison, New Jersey) provides great insight as does Craig Koshyk in a shorter account . The LM/Weimaraner pointing gene pattern was also found in samples from German Longhaired Pointers and English, Irish and Gordon setters. Spain, France and Germany were a hotbed for hunting dogs centuries ago. It is likely that the six breeds listed above share a common origin tracing back to the Hühnerhund or spaniel of that time.

In all likelihood, strategic crosses between dog types were made at that time. Animal breeding was sufficiently far advanced however, so that breeders knew that a breed's strength could be mixed into oblivion with careless crossing. Also, no breeder wants to see malformed puppies or hear from owners trying to cope with a dog out of balance. Crossing is the easy part, the painstaking work that comes afterwards to return to a hoped for balance and consistency in type is much more difficult. Some versatile breeds today have a more recent history of reintroductions than others.

The clubs for the LM and its sister breed, the German Long-haired pointer, have periodically introduced dogs from one-another to widen their gene pools. In the most recent of such efforts, the clubs could not agree on strategy and hence the German Longhair Club introduced German Shorthairs instead of Large Munsterlanders. To their surprise the plan did not go nearly as well as it had when using LMs before. The German Longhair breeders had to reject more of the offspring before they could be satisfied with the crossing outcome, as described by Markus Wörmann (2005, Wild und Hund #21, 71-72). Theirs was a mix across the hound/spaniel divide with less desirable outcomes.

In North America, without a strong tradition of originating dog breeds, and without the institutional tools to protect dogs, breeders and owners, ego-boosting adventures into crossbreeding are common. Here, as H.L. Betten describes it, "we merely imitate – we do not originate" (1945, "Upland game shooting", Alfred A. Knopf, New York).

Two of the pups above, Cue and Dryas, were entered in the HAE test at the tender age of 6 months. They both proved their well-bred heritage and passed a test of hunting aptitude offered for young dogs by the Versatile Hunting Dog Federation. In the coming year, they will likely be entered in the Advanced Hunting Aptitude Evaluation. There they will need to show not only the proper workings of their pointing gene but most importantly how a host of hunting dog traits, including temperament, need to be kept in balance. Such long-term working-dog consistency and balance are not built by one breeder, but are the achievement of a community of breeders working toward a common goal. So they have done beginning with the Hühnerhund to give us a remarkably fine-tuned dog that we are able to enjoy in the fields today.

|

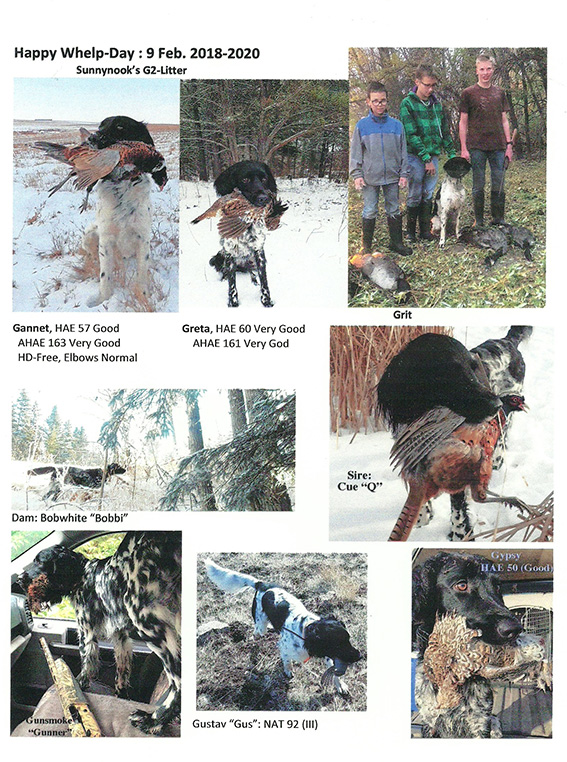

This drawing was likely pre-planned by the artist to show several characteristics at once, of the time represented. The gun resembles an early shotgun that could be swung and used on moving small game in the 1700s. One of the dogs is shorthaired, suggesting a hound. It is on a lead, content to stay by the hunter. The other two are a large and a small bouncy type, longhaired and keen to go with the flush. The dogs resemble the two broad sources that were to help form the German versatile dogs of today. This time signals a gradual shift in dog use. Prior to gun hunting, the spaniels were used prominently in falconry where the dogs needed to flush for the falcon to begin the chase. Some spaniels of the 'setting' type were used with nets to capture birds the dogs first located. The hound, prior to gun use, was used to track and then 'point out' big game in resting cover in preparation for the next day's driven hunt. These hounds were called "Leithunde" (leading dogs) or lymers in English.

-- Artist is in dispute, but likely Johann Elias Ridinger who lived in Augsburg from 1695-1769. Ridinger was well known for his many representations of hunting scenes. |

by Joe Schmutz, 14 Nov 2015

A working girl!

Sunnynook's Bobwhite "Bobbie" loves to come on the mailbox run. The 12 km run seems not to tax her 8 month old joints too much judging from her lead being the same on the way out or home. Besides learning to love water from the melting snow in the ditches, she is learning another lesson. Bobbie naturally started to pick up the beer and juice cans that others rudely tossed out their vehicle window. So, here is our strategy for teaching her without her knowing she's being thought.

Teaching a dog when it hardly knows it is being trained, is a key message of Joan Bailey in her 2008 book "How to help gun dogs train themselves, taking advantage of early, conditioned learning". Swan Valley Press, Portland, Oregon. Bobbie has learned to love to retrieve, to hold when coming without dropping, to trust that I respect her prize for a time at least, and to give when encouraged when she's getting close to loosing interest in holding anyway – before she drops it. One has to read one's dog to get the timing right. Besides learning, and here is the working part, for two cans that day with 10 cents/can, Bobbie has earned 20 cents toward her dog food. On her bonanza days, she earns 60 cents!

Back to Sunnynook Homepage

Please direct general questions about the content of this page to: e-mail sheila.schmutz@usask.ca